Intravenous access devices

We discussed intravenous access techniques briefly on the previous page, but we'd now like to look at this in more detail. One of the potentially confusing things that you need to understand as a hospital pharmacist, is the various devices used to deliver intravenous medicines into the body. People will talk to you about Venflons, Hickman lines, triple-lumen catheters and many others. What do they all mean? On this page we hope to explain for you, using example pictures.

Peripheral intravenous access

1. Cannula - this is commonly called a 'Venflon' but that is actually a brand name. The cannula can be inserted into a vein in the hand or arm and is for short-term use (days). Here is a close-up image:

|

| A peripheral intravenous cannula Courtesy of Fifo, Wikimedia Commons |

The needle helps to introduce a small plastic tube through the skin and into a vein; the needle is then removed. The plastic 'wings' enable the whole device to be securely taped to the skin. The pink plastic tap is a valve that can be turned open and the hole in the top allows a syringe to be connected to e.g. take a blood sample or administer an injection. The white 'luer lock' plug on the right-hand side at the end enables intravenous infusion lines to be connected. It's easier to appreciate the job that the peripheral cannula does when you see a picture of the device in situ:

|

| A peripheral cannula in situ © Crown copyright 2017 |

Notice that the short line connected to the luer lock branches into two so that two separate intravenous infusions can be connected. This is an example of a Y-site. Any medicines in the two infusions will be kept entirely separate until they reach the Y-site, after which they will mix before entering the patient.

In addition to a cannula, or sometimes instead, a patient may be fitted with one or more long lines at a different site. These are lengthy plastic catheters inserted into a vein but the tip is positioned some way away from the point of insertion. Some common examples are described below, with pictures. Note that 'long line' is a fairly imprecise phrase describing a variety of potential set ups. If you are ever unsure what someone means by the term, ask for clarification. It's often especially important for pharmacists to ask if a 'long line' is a peripheral line or a central line.

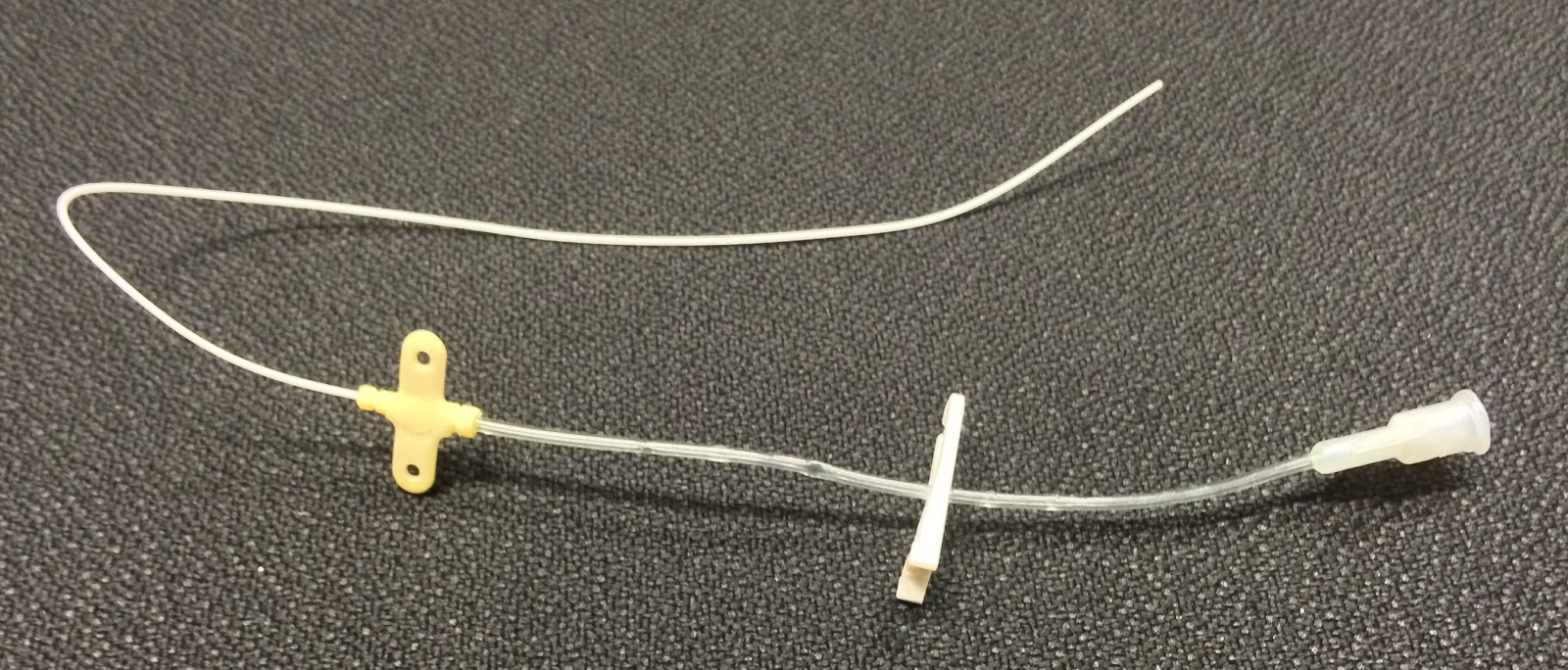

2. Midline intravenous catheter - this is a long peripheral intravenous line or 'catheter' generally inserted into an arm vein, but the tip of the catheter sits some distance away from where it enters the patient (e.g.in a larger vein near the shoulder). In the picture shown here the thin white catheter is inserted fully into the vein until the yellow butterfly on the left-hand side is reached, and this is then secured to the skin with tape. A midline catheter requires less frequent site change than a peripheral cannula and is less prone to causing phlebitis. However, it is still for short-term use (but often weeks rather than days).

Double lumen catheters that only have two lumens are also available, as are quadruple lumen catheters with four lumens and quin lumen lines with five lumens. These lines are commonly needed by intensive care and high dependency patients. One advantage of central administration is that irritant or vasoconstrictive drugs can be given more safely because of the wide diameter of the vein and the faster blood flow.

One of the most well-known examples of this type of central venous catheter is a Hickman line. It is inserted into the body at a site on the chest wall and is tunnelled under the skin until it reaches the neck. Then it enters a large vein such as the jugular vein and runs down into the superior vena cava. In our photograph you can just see the line running under the skin from its insertion point up towards the incision at the neck where the line will have been pushed into the jugular vein. Macmillan

Cancer Support has produced a helpful video

for patients

about having a tunnelled line inserted which you might like to watch.

Listen to Kathryn’s experience of

suffering paralysis and respiratory arrest after her intravenous line was not

flushed in theatre.

In addition to a cannula, or sometimes instead, a patient may be fitted with one or more long lines at a different site. These are lengthy plastic catheters inserted into a vein but the tip is positioned some way away from the point of insertion. Some common examples are described below, with pictures. Note that 'long line' is a fairly imprecise phrase describing a variety of potential set ups. If you are ever unsure what someone means by the term, ask for clarification. It's often especially important for pharmacists to ask if a 'long line' is a peripheral line or a central line.

2. Midline intravenous catheter - this is a long peripheral intravenous line or 'catheter' generally inserted into an arm vein, but the tip of the catheter sits some distance away from where it enters the patient (e.g.in a larger vein near the shoulder). In the picture shown here the thin white catheter is inserted fully into the vein until the yellow butterfly on the left-hand side is reached, and this is then secured to the skin with tape. A midline catheter requires less frequent site change than a peripheral cannula and is less prone to causing phlebitis. However, it is still for short-term use (but often weeks rather than days).

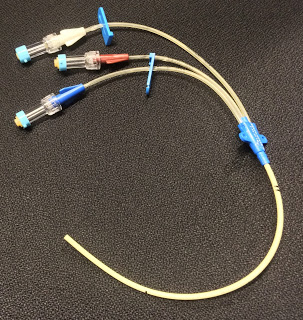

Central intravenous access

1. Short term access - this is often achieved by a multi-lumen central line with separate tubes running the length of the catheter. It is inserted into a large vein such as the internal jugular vein and the tip ends up in the distal superior vena cava just outside the heart. As you can see from the photo and diagram of a triple lumen catheter below, the lumens are effectively separate catheters bound together. Medicines that enter via one lumen do not mix in the catheter with medicines administered via one of the other lumens. The lumens exit the catheter at different points along its length and any medicines administered down them are rapidly diluted by the fast-flowing bloodstream. This

allows incompatible medicines to be given simultaneously.

2. Longer-term venous access - there are a number of ways to achieve this, using an intravenous device that can stay in place for months or more, and three examples are given below.

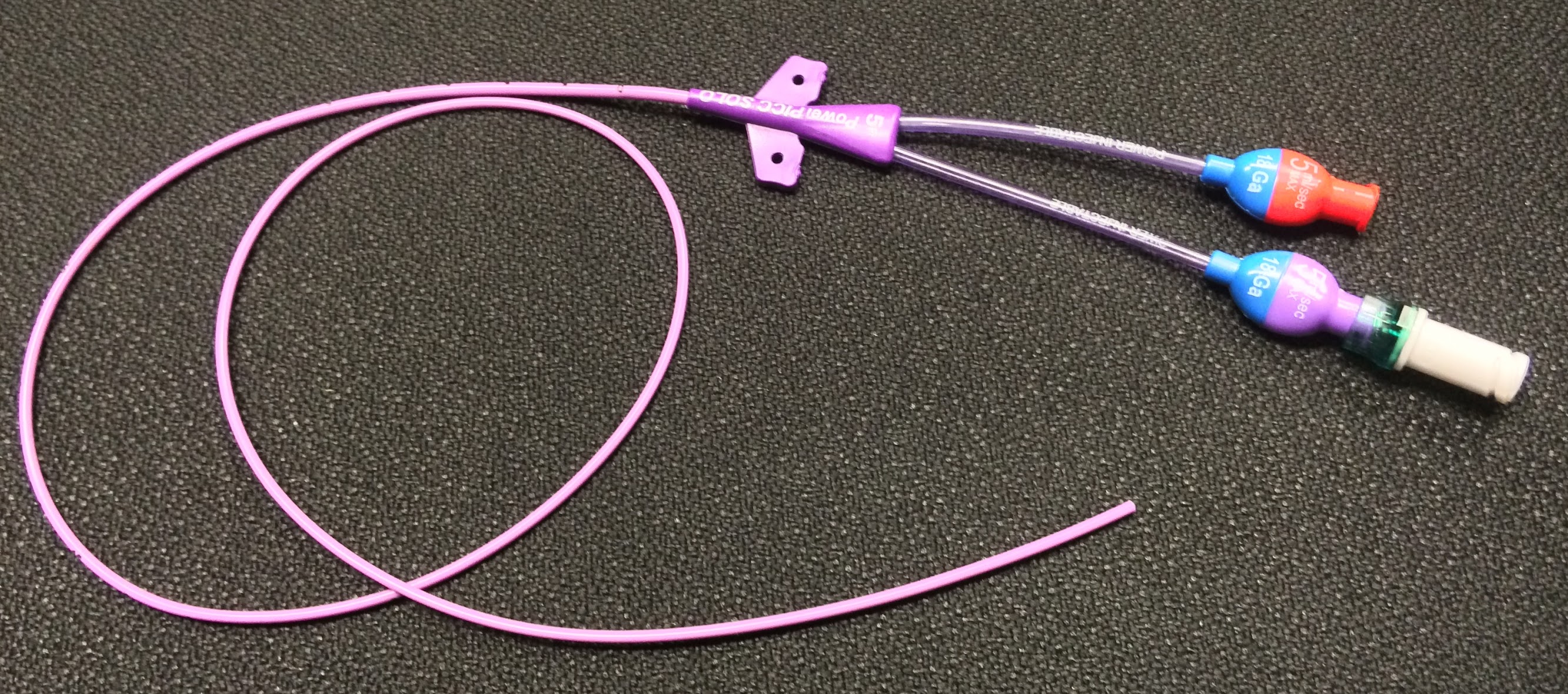

a) PICC line

This stands for Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter, and although it's inserted at a peripheral location the tip of the catheter resides centrally (e.g. in the superior vena cava). A PICC line is intended to stay in place for long periods (months) and is used, for example, for administering prolonged chemotherapy regimens or TPN. These lines are relatively straightforward to insert compared to some of the alternatives below, and can be single, double or triple lumen.b) Totally implantable devices

These devices are implanted beneath the skin somewhere on the chest wall in a pocket of skin (e.g. near the collar bone) or on/under the upper arm, depending on patient choice. The catheter is fed into a central vein, and the port allowing access to the catheter is positioned just below the skin. When an injection is required a special 'non-coring' needle is inserted through the skin and then through a self-sealing rubbery membrane in the port (called a septum).

The photographs show an example known as a portacath with the port at its head. The photo on the right-hand side (courtesy Pixman, Wikimedia Commons) is an X-ray showing the portacath in position in a patient. Patients who require long-term repeat injections may have a portacath e.g. people with cystic fibrosis or on chemotherapy. These types of device can be left in place for a long time but are more cosmetically acceptable and pose a lower infection risk.

c) Tunnelled and cuffed central catheter

|

| Courtesy of General Ludd Wikimedia Commons |

Hickman lines are used for long-term intravenous administration of medicines such as chemotherapy. Hickman lines, PICC lines, and portacaths might all be used by patients receiving long-term intravenous therapy at home.

Finally, this diagram illustrates a method by which IV access devices can be selected in practice; it is included here courtesy of the originator, Katie Scales, and the NHS Injectable Medicine Guide.

Finally, this diagram illustrates a method by which IV access devices can be selected in practice; it is included here courtesy of the originator, Katie Scales, and the NHS Injectable Medicine Guide.

Flushing administration lines

Intravenous lines must be flushed

before and after the administration of

medicines to prevent potentially incompatible drugs from mixing. Flushing

should also occur at the end of surgical procedures to ensure that

perioperative medicines such as anaesthetics are not left in the line when the

patient returns to the ward. In patients who have long-term intravenous lines

inserted, flushing helps to prevent the line from blocking, maintaining their

‘patency’.

Flushes should be compatible with the

medicine being administered; the most commonly used in practice are water for

injection and sodium chloride 0.9%.